6 • School Bus

Zodiac is making threats which now target children. And he says he’s making a bomb.

There’s nothing like the hysteria and paranoia of a parent fearing for their child’s life. The Zodiac preyed on hysteria and fear, like the Joker from Batman.

This whole dilemma of should journalists concern themselves with simply informing the public with relevant information, or should they concern themselves with the effects of their reporting? It’s a really, really problematic dilemma.

– Adam Ragusea, professor of journalism at Mercer University

School children make nice targets, I think I shall wipe out a school bus some morning.

Transcript

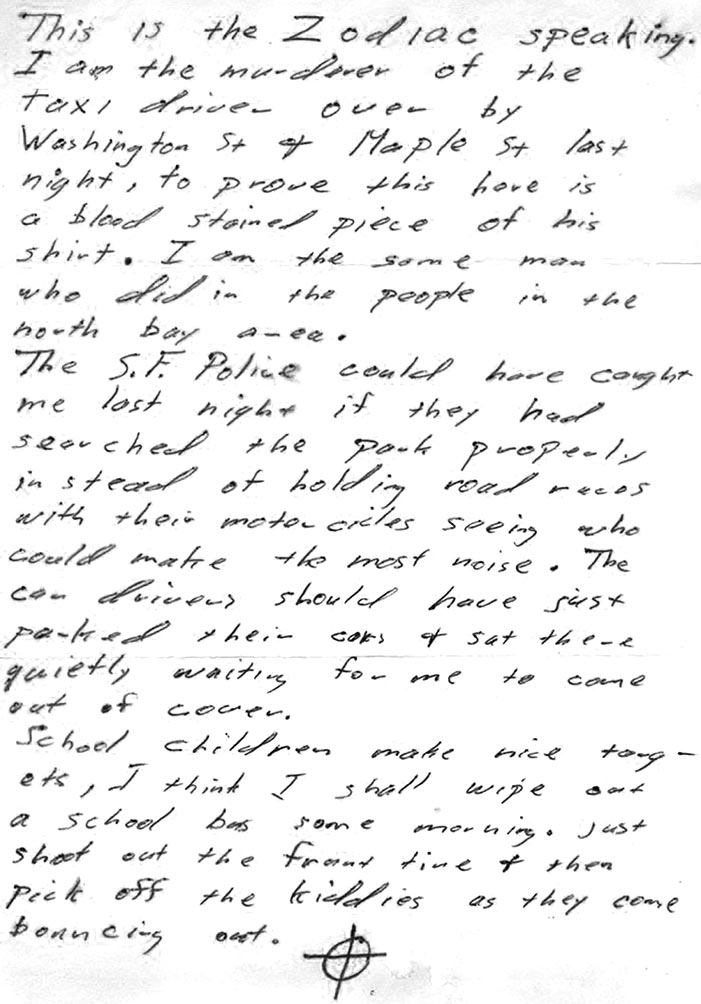

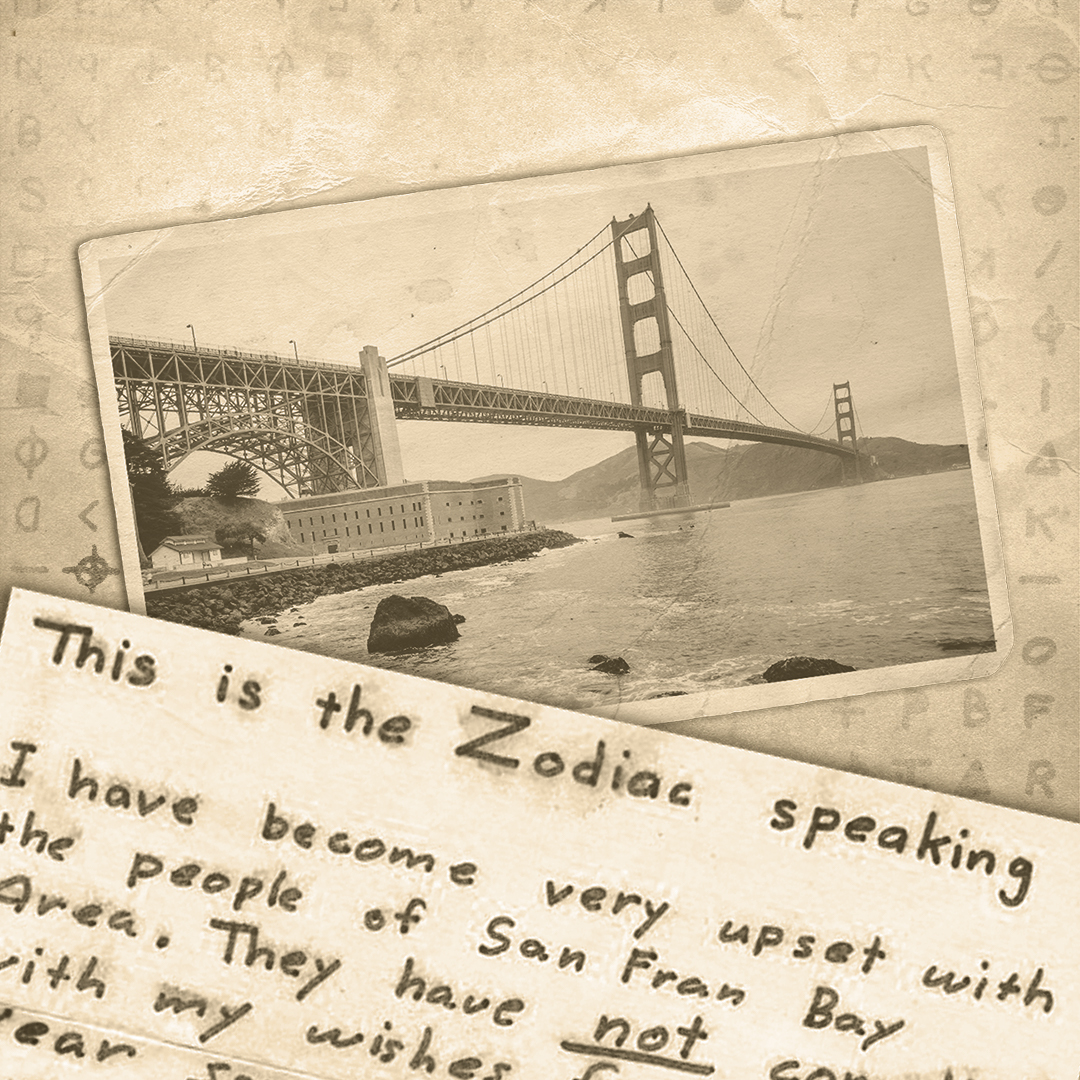

Speaker 1: The Zodiac was now in San Francisco. He had killed a cab driver and took credit for the murder in a new letter. Inside, a piece of bloody cloth from the cab driver’s shirt. The Zodiac now had the city’s attention, and he gripped the entire Bay Area in fear with his deadly game. It was clear that anyone could be next. People walked the streets with caution as they went about their everyday lives. But as Michael Butterfield says, “Paul Stein’s murder wasn’t the most terrifying detail. For the first time, the Zodiac has included a very real threat.”

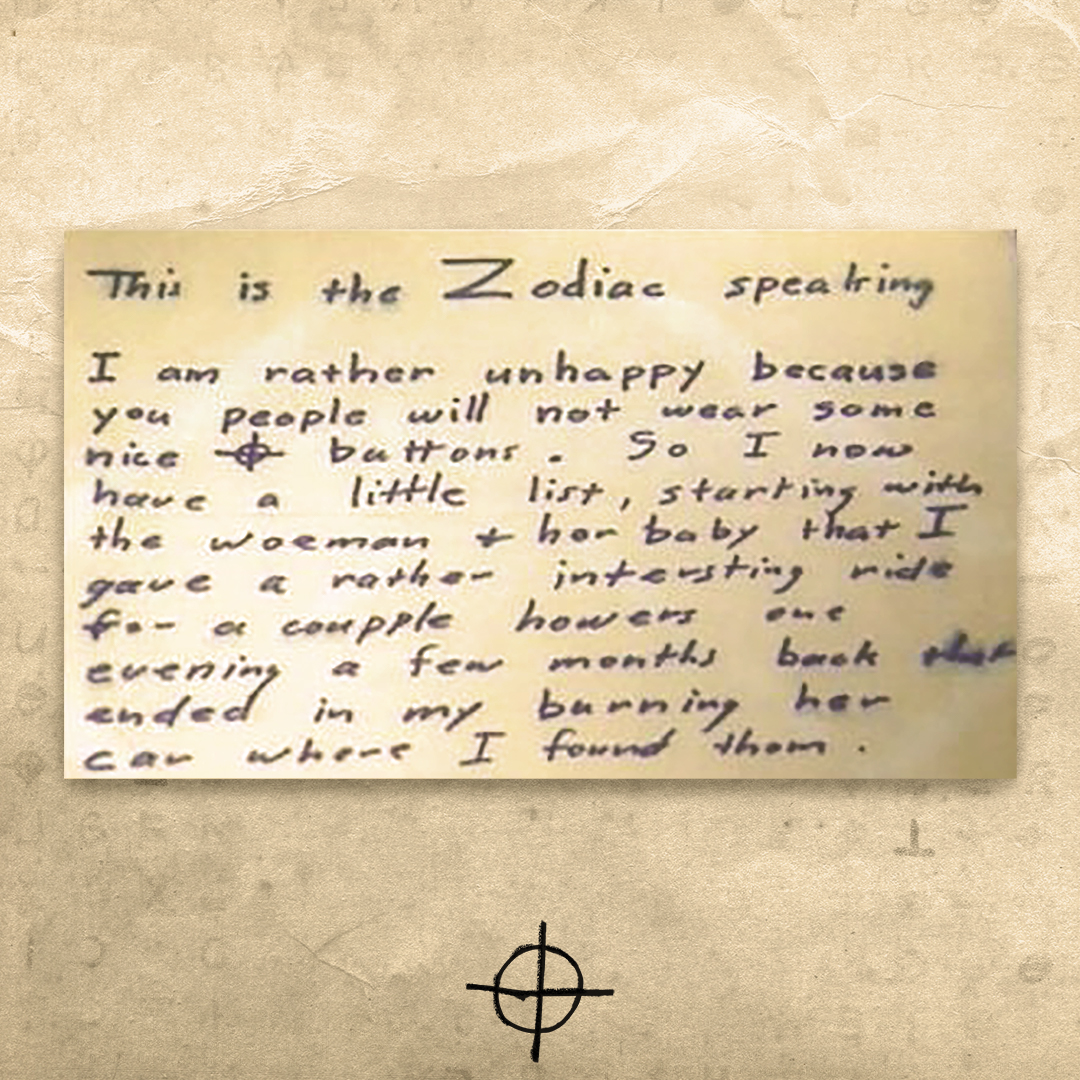

Speaker 2: Schoolchildren make nice targets. I think I shall wipe out a school bus some morning. Just shoot out the front tire and then pick off the kiddies as they come bouncing out. Signed, Zodiac.

Speaker 3: This was, of course, terrifying because he had already demonstrated that he was capable of extreme acts of violence, and now he was threatening schoolchildren. The fact that he had moved to a major metropolitan city and murdered a cab driver for no apparent reason, which was completely outside of his previous victim preference, indicated that this man was very unpredictable. And when he started threatening schoolchildren, there was no reason to believe that he was bluffing.

Speaker 4: In San Francisco, we have been, since the first day, since the reception of this note, we have a number of plainclothes officers following buses in the morning and in the evening.

Speaker 3: So there was a concerted effort to protect school children on school buses and all around the Bay Area. There were police officers that were following the buses, police officers, sheriff’s deputies who were assigned to ride on the buses with shotguns. There were helicopters following buses. And bus drivers were given instructions on what to do in the event that someone did shoot at them.

continue reading

Speaker 5: We have specifically requested that they alert their drivers to not stop under any conditions if a shot is fired or if the bus is subjected to a flat tire by this sniper. Further, that they get the children down immediately and proceed with all speed out of the area. To try and attract all the possible attention by blowing their horns. Therefore, get out of the situation.

Speaker 3: So every effort was made to avoid the scenario that the Zodiac preferred. And that, of course, created a rather traumatic childhood for a lot of children that were growing up in the Bay Area, and who at this time now remember him as some sort of boogie man who scared them to death.

Speaker 6: I heard this loud shot from the left-hand side of the bus.

Speaker 7: What did the children do?

Speaker 6: They heard it. My reaction was get them off the bus, get them in the school as fast as I could. And I was right behind them.

Speaker 3: Now conversely, there’s also a great piece of video from that period, a piece of film footage shot by a local news station where they’re interviewing one of the bus drivers.

Speaker 8: Have any of the drivers expressed any concern over their job now?

Speaker 9: There’s naturally talk. Everybody’s I guess tense about it. But they all seem to be in good spirits. They all seem to be going on with the job. I don’t know of anybody that’s quit.

Speaker 3: And the bus driver is saying “Well, you know, I’m not really that concerned about it, or whatever. But we’re going to be careful.” And in the background, there’s a little kid who shouts out …

Speaker 8: You’re not afraid?

Speaker 10: No, I’m not.

Speaker 9: No, he’s not-

Speaker 9: Not too afraid.

Speaker 3: And it kind of puts things in perspective for you that children really didn’t understand what was going on. They knew enough to be scared, and they knew enough that there was something happening around them, but they had no concept like the adults did of what was really going on. The children just knew someone was threatening them. The adults knew that they were being threatened by a man that had already killed before and was perfectly capable of doing it again. So that bus threat changed everything in the case. It not only terrified people and created this whole situation where they’d have to protect children all over the Bay Area, but it also elevated the Zodiac to a level he had not been at before, which was someone who could attack anyone at any time.

Speaker 11: A man in a mask, robbed, tied and stabbed them, leaving them for dead.

Speaker 12: Subject stated “I want to report a murder. No, a double murder. I did it.”

Speaker 13: A man who wore a medieval-style executioner’s hood, carried a knife and gun and intended to use them.

Speaker 14: They haven’t arrested me because they can’t prove a thing. I’m not the damn Zodiac.

Speaker 15: Who is the Zodiac, and where is he?

Speaker 3: From iHeartRadio, HowStuffWorks, and Tenderfoot TV, this is Monster: The Zodiac Killer.

Speaker 3: There’s nothing like the hysteria and paranoia of a parent fearing for their child’s life. The Zodiac preyed on hysteria and fear, like the Joker from Batman. Fear made him feel powerful, and it created a difficult problem for journalists and civic figures. Should one continue reporting the misdeeds of the Zodiac? Or does that only fuel him? Is that doing what he wants? The worst part about fear mongering is that a bomb doesn’t even have to be there to accomplish the goal of mayhem.

Speaker 1: Zodiac’s threat to harm schoolchildren created a ripple effect across the Bay Area. In Vallejo, the local community was still reeling from the recent attacks. It had only been a few months since the Zodiac killed Darlene Ferrin at Blue Rock Springs. Now Vallejo police were also taking precautions to protect school buses. While San Francisco was no stranger to high-pressure situations, Vallejo was different, suburban, quiet.

Mark: Back then, Vallejo was a really, really nice town, nice place to live. Me and my little sister walked to school all the time. It was right along Snowman Boulevard there at seven, eight years old and nobody thought anything of it. My name is Mark Gibner, I’m 56. I live in Loomis, California and I was born and raised in Vallejo. In the neighborhood that we lived in, California Meadows, we had a huge, huge field or lot. As kids, we could just go play around, collect ladybugs and a lot of friends. We’d just go ride bikes and do kid things. I’d be five, six years old and be gone for hours with my friends in the neighborhood and out in that field and I don’t think my mom ever had any worry about that until …

Speaker 18: Just shoot out the front tire and then pick off the kiddies as they come bouncing out.

Mark: I remember as a kid, having a cop car follow behind us and I remember that because as kids, we would all kind of run to the back of the bus and wave at the cop out the back window of the bus. And then certainly for a couple of years, our trick-or-treating had to be in the daylight, obviously, with adults.

Speaker 19: What is most noticeable is the lack of teenagers and young people out at night or in the weekends. It seems that the parents are keeping the children home.

Mark: I don’t have a recollection of saying “The Zodiac Killer is out there.” I heard the name. I just knew that there was something going on. You’d see the headlines in the Vallejo Times-Herald. Nobody was really thinking about a serial killer so much, as just a couple people that were murdered. I think that started taking on that life in the following years.

Jim: There’s a lot of Vallejoans who have been here for generations. A lot of them, of course, worked at Mare Island at the shipyard. And so even though we’re in a major metropolitan area, especially I think at that time, it really had kind of a small town feel to it. Just another typical suburb, which is why I think the events with the Zodiac were so surprising, because it doesn’t seem like the kind of thing that would happen in a town like Vallejo.

Jim: My name is Jim Kern. I’m the Executive Director of the Vallejo Naval and Historical Museum. You hear about murders and violence, and it’s always been, unfortunately, a part of human nature. But sometimes it takes place in an environment that’s a little scarier or something that’s not germane to people’s everyday lives. So this was different because this was just everyday people that might have been your next door neighbors and suddenly it’s right here in your town. So that makes it quite a bit more scary.

Jim: There’s always been murders, and there’s always scandals and crimes, and the people are interested in that kind of thing. People are kind of fascinated by it. But I think the fascination is when they can read about it or see a movie or when it’s sort of one or two or three steps removed from their everyday life. But suddenly when it’s happening all around you, that’s a different thing altogether, and it’s no longer quite so fascinating. It becomes more terrifying.

Speaker 1: Vallejo would be forever changed by this chapter. That feeling of small-town charm had begun to fade, and maybe that’s exactly what the Zodiac wanted. In San Francisco, police took these threats even more seriously. Patrols followed dozens of buses on their routes each morning and afternoon, and this lasted for months. To achieve this, police had to dedicate a huge amount of manpower, and this got me thinking. Could they pull that off today? And if not, how would San Francisco officials respond to such a threat?

Paul: The response nowadays would be very different from what we probably saw in the late 60s with regards to manpower and being able to have the people to do that would be very tough. My name is Paul Quesada, and I’m the Director or Crisis Response and Emergency Preparedness for the San Francisco Unified School District. Crisis response is being able to deal with the day to day issues that might be affecting our schools. There’s a case, an example that I share with my staff. Two teachers were onsite supervising. One of them heard loud pops from a distance. She had no idea what it was. But it felt wrong to her. She had never heard it before. The pops were getting closer, and she felt we need to move the kids inside. And so she did. Small school. Maybe 100, 130 kids there. And it was a gentleman who had gone out in his vehicle and was shooting at anything he could and pulled up into the school and fortunately no one was out there because the teacher brought everyone inside.

Speaker 1: Paul Quesada deals with situations like these every year. However, he had never heard of anything like Zodiac’s threat to shoot a school bus. These days, school threats are very different.

Speaker 22: We’re following that breaking news story for you out of Texas this hour. Police have confirmed there are multiple casualties at a local high school in Santa Fe, which is south of Houston.

Paul: These unfortunate things have been happening for years, right? And usually, the warning comes from the sounds of gunfire, or the voices in distress, or what have you. I think information is always key for all of us. And I think when people don’t have it, that’s when panic mode tends to kick in.

Speaker 1: Luckily, Paul Quesada says the response time of law enforcement has only gotten better. That’s due in large part of advancements in technology.

Paul: There was no mass way of getting this information out quickly. You got to put it in the newspaper, print it, and send it out, and then you have to hope you have people buying the press to be able to see it. I think today, given our technology where we can send out a quick message to everybody, a mass message … I mean, heck, we can send out a message and a phone call to all 57,000 of our students in a matter of two seconds. It’s impressive how we can do that now, versus back then when you weren’t able to do that.

Duffy: So the first letter came and was printed in the Sunday paper. And when the second letters came, we printed our story, and the Examiner printed their story.

Speaker 1: Remember Duffy Jennings? He was a copy boy who became a crime reporter for the San Francisco Chronicle. I met up with him at a park near his home.

Duffy: You know, I still don’t have a sense that this was the biggest story of the day, but it was decided that yes, there’s a bonafide threat. There’s evidence that whoever wrote this letter committed these shootings and we better take it seriously enough that if we don’t print it and he does take out a school bus full of kids, and they find out that we knew about it ahead of time, didn’t tell anybody, it’s that same dilemma that editors go through every day. Is it in the public interest and benefit to publish this even though it might panic people? And the decision was made, that in the interest of public safety, it was sort of compelling to publish the threat so people could take their own measures as they saw fit. And it did panic people. A lot of kids were kept home from school or at least kept off their school bus. Parents were walking their kids to school or driving them to school and buses were empty to a large degree just because of this. So that was the impact, but I don’t remember it as a story that had a lot of legs. There was a follow up the next day and the next day and the next day as big stories tend to do.

Duffy: Also in 1970, ’71, there was the kidnap of the Chowchilla school bus out in the Central Valley where three guys commandeered a school bus with 26 kids on it, aged five to 14, took the bus to a quarry in Livermore and buried it for several days until the driver and the kids were able to dig their way out. And the three guys who did it went to prison. So the Zodiac wasn’t the only sort of school bus situation that occurred then. Here was a guy who learned to manipulate the media, threaten public safety and nobody knew where the next attack was going to come from. Now we have, in my view, one of the early terrorists.

Speaker 1: The Zodiac’s threat to shoot kids on a school bus was only the beginning.

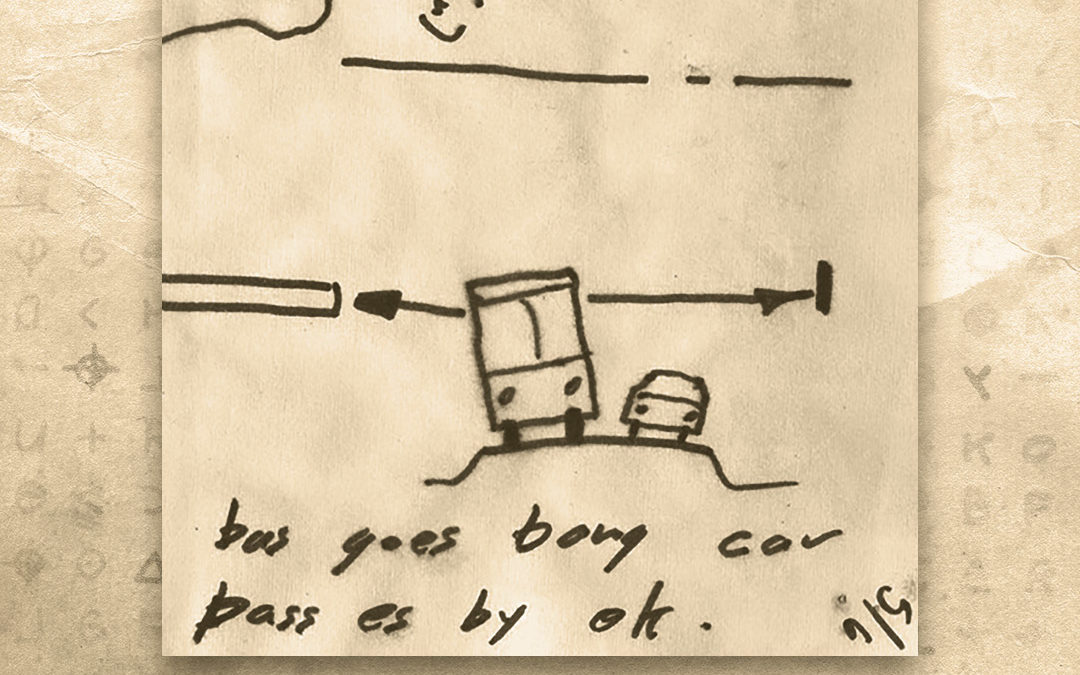

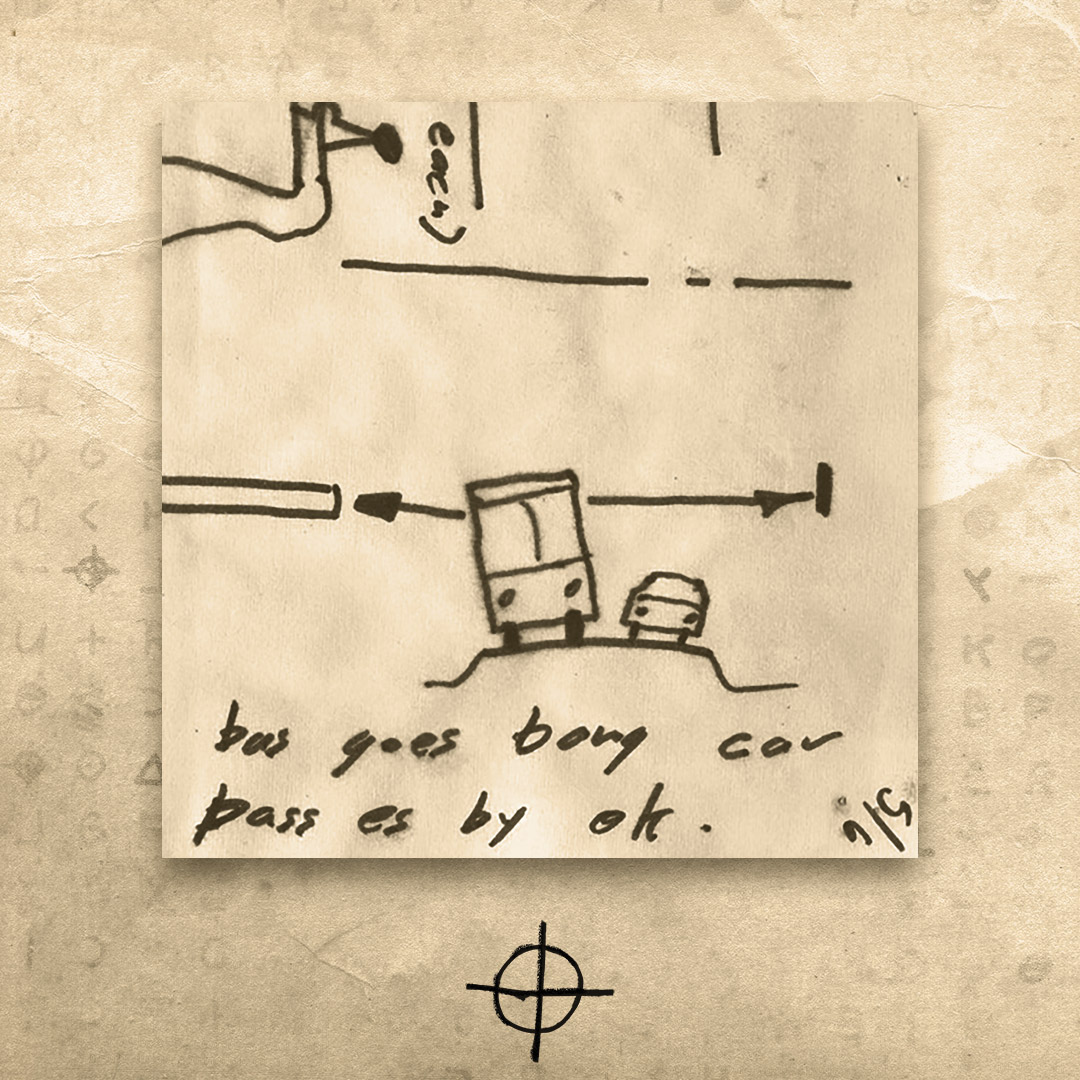

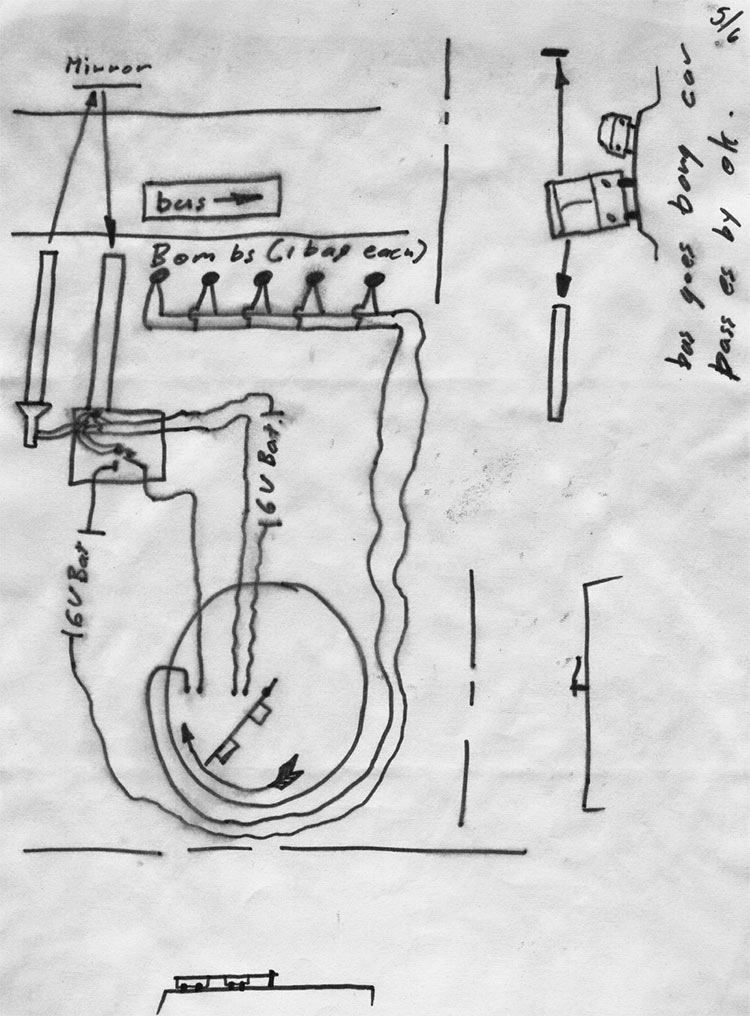

Duffy: Once he had committed his murders and started writing his letters and terrifying people and then he started threatening to shoot schoolchildren and things, that wasn’t enough for him. Then he moved onto the next level, where he started threatening to blow up a school bus full of children. He claimed that he had planted bombs along roadsides that would take out a school bus full of kids. He would send these diagrams, these elaborate drawings of these bombs. He would describe the ingredients that were going to be used, and he referred to this as his death machine.

Speaker 2: The death machine is already made. I would have sent you pictures, but you would be nasty enough to trace them back to the developer and then to me. So I shall describe my masterpiece to you. Take one bag on ammonium nitrate fertilizer and one gallon of stove oil …

Speaker 1: Again, the San Francisco Chronicle had a difficult choice to make. Would they publish the Zodiac’s threat or not? The Chronicle decided not to publish.

Peter: I think it’s extremely unnerving to think that there’s somebody out there preying on young people, more or less randomly. And then taunting the culture at large through the media.

Speaker 1: This is Peter Richardson, historian, and lecturer at San Francisco State University.

Peter: I mean, if you want to compare it to a similar case, you can think of the abduction of Patty Hearst.

Speaker 25: Good evening. Patty Hearst has been taken into custody. The FBI says Patty Hearst was picked up today in San Francisco. The Hearst newspaper heiress has been missing for 19 months. First, she was kidnapped, then she announced that she had joined ranks with her kidnappers, members of the Symbionese Liberation Army. She called herself Tanya. She was later indicted in connection with the San Francisco bank holdup and labeled a fugitive.

Peter: With the abduction of the granddaughter of this great media titan, William Randolph Hearst and her father, who was still connected with the San Francisco Examiner, the media frenzy that resulted, predictable as it was, was a huge part of the story itself. So in some ways, we start to see the media become a player in the stories that they’re covering, partly because it had to do with the media. And I think that was really true of both with the Zodiac, but also with the Patty Hearst abduction. Whether or not the media made the right call there, I know they struggled with it. It’s not obvious that you want to turn your newspaper over to a nut and let him communicate directly with your readers. We see that again with the Unabomber case.

Speaker 26: On January 22nd, 1998, the Unabomber, Ted Kaczynski, pleaded guilty to avoid the death penalty. Kaczynski sent 16 mail bombs to universities and airlines over a 17 year period, killing three people and injuring 24. Before his arrest in 1995, the Washington Post and New York Times reluctantly printed his 35,000-word manifesto under threat Kaczynski would strike again if they didn’t.

Peter: Which turns out to be the key to the arrest made in the Unabomber case because somebody realizes “Hey, that letter, they writing sounds a lot like my brother’s.” So you could make arguments both ways, I think. If you let this information out, you might get new information from somebody that says “Boy, that sounds like …” You might get leads that way. But there’s a real risk, because if you know that your perpetrator is kind of getting energy from this and that it becomes something that he wants to keep doing if you open that door, then you really have a kind of moral decision and a moral responsibility if you’re the media.

Adam: When it comes to the ethics governing how you report on serial killers, terrorists, mass shooters, there’s tons and tons of journal articles written by people trying to assert certain journalistic codes of conduct and stuff like that, but there’s no clear consensus because it’s so incredibly debatable.

Speaker 1: Adam Ragusea is a professor of journalism at Mercer University.

Adam: So many of the arguments about how you should absolutely publish this, or you shouldn’t publish that are predicated on unprovable counterfactuals, right? Like it asks us to believe that if a newspaper hadn’t published a thing, then somebody wouldn’t have gotten killed. Well, we can’t know that. And then there’s another point of view that says no, no, no, no, no. We shouldn’t concern ourselves with outcomes in journalism. That’s not our job. We’re not activists, and we’re not cops, right? We’re journalists. Our job is to put information out there. If it’s relevant if it’s newsworthy, then you put it out there, and then you let the chips fall where they may. There’s other people whose job it is to concern themselves with the outcomes. Your job is to get the information out there.

Adam: And I’m not saying you never withhold stuff, but I think if you are going to withhold information, it’s got to be because there’s an immediate, direct threat to somebody’s life that would be posed by publishing that information or some very specific way in which publishing that information would sabotage a police investigation. When there’s a really direct line that you can draw, that’s when you hold back information, but if it’s just sort of vague, then I think you put it out there. And I also don’t think you should necessarily trust what the cops say because police and government agencies, they have sort of a bias towards secrecy. They really do. And they will sometimes ask you to not publish something and if you try to interrogate them as to why they don’t even really have a good answer. It’s just they have a bias towards secrecy. So unless they can give you a really good answer, no, you publish because that’s what you do. You’re concerned more with matters spiritual than matters temporal, meaning you’re concerned more with informing the public than with how that information may be used out there in the world.

Speaker 3: These bombs, they served the purpose of removing him from the equation. He doesn’t even have to be there anymore to kill you. That’s frightening. I’m just going to set this up, and someone’s going to die, and I won’t be anywhere near where this happened. And I think was part of a change in his MO to where he didn’t need to actually carry out a crime anymore to scare people and get attention. But now, he was creating crimes in your head. He was making you imagine what would happen. But people believed it could happen and that was all that mattered.

Speaker 1: Another letter concerning the bombs arrived at the Chronicle.

Speaker 2: I hope you enjoy yourselves when I have my blast. If you don’t want me to have this blast, you must tell everyone about the bus bomb with all the details.

Speaker 1: Now there was a direct threat. The Zodiac said he’d put the bomb to use if the Chronicle didn’t write about it. And this time, the paper decided that they had to publish. But they didn’t publish everything.

Adam: This whole dilemma of should journalists concern themselves with simply informing the public with relevant information, or should they concern themselves with the effects of their reporting? It’s a really, really problematic dilemma. There’s no clear answer about it. But maybe things get a little bit clearer when you start talking about things like bomb recipes, you know? It seems like it’s a pretty clear case of journalism ethics that you don’t publish a bomb recipe unless the bomb recipe is inherently newsworthy in some way, because you can have a reasonable degree of confidence in thinking that if anyone is going to use that for anything, it’s going to build a freaking bomb and kill people, right? There’s no conceivable, legitimate way of using that information.

Speaker 1: The San Francisco Chronicle decided to omit the Zodiac’s bomb recipes and specifications. Even though he demanded they quote “publish all the details.”

Adam: You’ve got to ask yourself, what’s the moral likely scenario here? That this guy who has killed a bunch of people is going to kill somebody again, or that somebody’s going to build this bomb from this creepy recipe and kill somebody? I don’t know. I kind of feel like the former is the more likely scenario. I don’t think that this scenario would even present itself today, but let’s imagine that it did. Zodiac killer is sending me a whole bunch of stuff to my newspaper and asking me to publish it, and I’m trying to decide whether or not I should publish it. I feel like the calculus would be a little bit different because I would know that this stuff would get out anyway. Like the public is going to get access to this information, investigators are going to find it. I have to publish it. I, as a professional journalist, am less of a direct and crucial line of information today than I was in the 70s, right? This stuff is going to get out there. What’s up to me is whether or not I boost this killer’s notoriety. It’s whether I amplify the signal of this bomb recipe. It’s going to be on the internet regardless.

Adam: If you’re a serial killer and you want to get your message out there, you could just post it pretty much anywhere on the internet today and have a reasonable degree of confidence that people would go and find it and disseminate it after you had done your deed. I think violence is inherently powerful. Violence is power. There’s no way to take power away from violence. Anyone who is willing to wield terrible violence will acquire power as a result. There’s nothing that people in the media can do to neutralize that effect. If people want to kill somebody, they’re going to gain notoriety, whether we publish their face or not.

Speaker 1: Would the Zodiac be satisfied without the public knowing all about this death machine?

Speaker 2: What you do not know is whether the death machine is at the site or whether it is being stored in my basement for future use. I think you do not have the manpower to stop this one by continually searching the roadsides looking for this thing. And it won’t do to reroute and reschedule the buses. It could be rather messy if you try to bluff me. P.S., be sure to print the part I marked out on page three, or I shall do my thing.

Speaker 1: Next time on Monster: The Zodiac Killer.

Speaker 28: I’m going to kill those kids.

Speaker 29: Today there was a possibly significant development. This morning the people of San Francisco heard a man who claimed to be Zodiac talking on the air.

Speaker 30: In my opinion [inaudible] have a cup of coffee. I don’t really know. The only thing I can conclude is it sounded like a fellow who does have a pretty serious problem.

Duffy: During the course of my couple years as a copy boy, I got to know all the reporters pretty well, and that included Paul Avery. Whenever I went out of the building with Paul, I had to kind of look around. Paul started to wear a holster. He got a handgun permit from the police chief.

Speaker 2: Dear Melvin, this is the Zodiac speaking. Please help me. I cannot reach out for help because this thing in me won’t let me. I’m afraid I will lose control again and take my ninth and possibly 10th victim. I am drowning. At the moment, the children are safe from the bomb, but if I hold back too long from number nine, I will lose complete all control of myself. Please help me. Signed, Zodiac.

Speaker 1: Monster: The Zodiac Killer is a 15-episode podcast produced by iHeartRadio, HowStuffWorks and Tenderfoot TV. Donald Albright and I are executive producers on behalf of Tenderfoot TV, alongside producers Meredith Stedman, Mason Lindsey, and Christina Dana. Jason Hoch is executive producer on behalf of How Stuff Works, along with producers Trevor Young, Miranda Hawkins, Ben Kuebrich and Josh Thane. Scott Benjamin provides additional voice talent. Matt Frederick is our host. Original music is by Makeup and Vanity Set. If you haven’t already, make sure to check out the first season of Monster, called Atlanta Monster, about the Atlanta Child Murders in the late-70s to the early-80s. Download the 10 episode season right now. Have questions or comments? Email us at monster@howstuffworks.com. Or you can call us at 1-833-285-6667. Thanks for listening.

Episodes

7 · Prime Time

After an impromptu TV appearance, the Zodiac fights to stay in the limelight.

8 · Origins

A close encounter with the Zodiac sends investigators to Riverside, California.

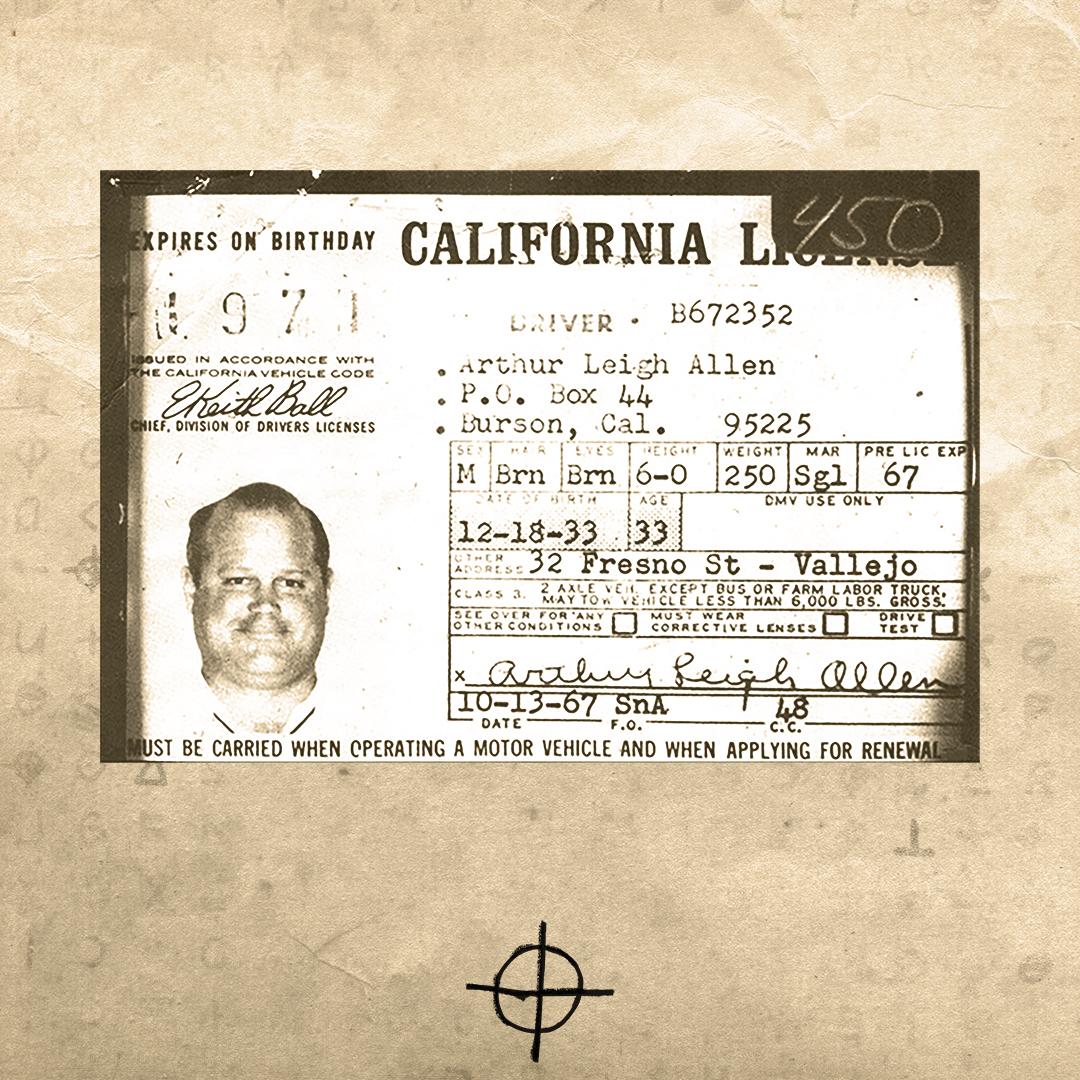

9 · Prime Suspect

Investigators finally put a name and face to the Zodiac. The prime suspect is revealed.